Art treasures of the Mughal empire

From the 16th to the 18th centuries, the Mughals dominated South Asia, and they took their art seriously. A new show of the empire's treasures is not to be missed, argues William Dalrymple

An elephant and its rider trampling a tiger, painted by Mir Kalan. Photograph: The British Library Board

The borderlands between Iran and Afghanistan have always been dangerous and marginal territory. Even today it is wild, remote country, haunted only by soaring hawks, packs of winter-wolves and opium smugglers working the old caravan routes. Four hundred years ago it was an area travellers tried to avoid at all costs.

Braving all this, in the early 1580s, the greatest Persian painter Farrukh Husain made the decision to leave his homeland and his appointment as court painter at the Saffavid court in Isfahan, to trudge over the barren desert hills and make his way into the dominions of the Great Mughals. The Persians traditionally disdained the Islamic courts of India: to Persian ears, the Indians spoke Persian badly, with a heavy accent. Their sense of aesthetics was quite different too. To Persian eyes, Indian art, and especially Mughal art, was too ripe and rounded, too bright and colourful, and lacked the classicism, restraint and geometric perfection of Saffavid painting. Indian fashions were even more offensive to Persian sensibilities. When the Persian intellectual Abdul Latif Shushtari arrived in India he recorded his horror, writing that he was "shocked to see men and women naked apart from a loin-cloth mixing in the streets and markets, as well as out in the country, like beasts or insects. I asked my host 'What on earth is this?' 'Just the locals,' he replied, 'They're all like that!'"

Yet for all his misgivings, Farrukh Husain had made a wise choice. After a spell working for the brother of the Emperor Akbar in Kabul, he headed on down to Agra, where Akbar (1542-1605) welcomed him. By 1585 he had ennobled him for his services to painting, giving him land, an honoured position at court and changing his name to Farrukh Beg – Lord Farrukh. He was also honoured with a prominent mention in the official biography of Akbar as one of the two greatest artists in a court that took its art very seriously. As the emperor's biographer, Abu'l Fazl, wrote, quoting Akbar himself: "More than a hundred painters have become famous masters of the art, while the number of those who approach perfection, or those who are middling, is very large … It would take too long to describe the excellence of each. My intention is 'to pluck a flower from every meadow, an ear from every sheaf'."

The Child Akbar Recognises His Mother. Photograph: The British Library Board

The Child Akbar Recognises His Mother. Photograph: The British Library Board

The Mughals, perhaps more than any other Islamic dynasty, made their love of the arts, their aesthetic principles, a central part of their identity as rulers. The second Mughal emperor, Humayun (1508-56) believed that artists "were the delight of all the world" and lured several Persian masters to his court from Persia and central Asia. His son, the emperor Akbar, did the same and emphasised that he had no time for ultra-orthodox Muslim opinion, which objected to the depiction of the human form: "There are many that hate painting," he wrote, "but such men I dislike. It appears to me as if a painter had a quite peculiar means of recognising God; for a painter in sketching anything that has life, and in devising its limbs, one after the other, must come to feel that he cannot bestow individuality upon his work, and is thus forced to think of God, the giver of life." It is one of the most eloquent defences of portraiture in the history of Islamic art.

The reigns of Akbar's son, Jahangir (1569-1627), and his grandson, Shah Jahan (1592-1666) saw the highpoint of Mughal portraiture, and with it the moment of greatest celebrity for the masters of the court atelier. Abu'l Hasan seems to have been a particular favourite of Jahangir. "I have always considered it my duty to give him much patronage," wrote the emperor in his autobiography, the Jahangirnama, "and from his youth until now I have patronised him so that his work has reached the level it has."

What drew Farrukh Husain and the other great painters of the age to Mughal service was less the good taste of the emperors than their incredible wealth. The Mughals were not just enthusiasts of the arts – they also had unrivalled resources with which to patronise them. They ruled over five times the population commanded by the Ottomans – some 100 million subjects – controlling almost all of what is now India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, as well as eastern Afghanistan.

A Panorama of Delhi by Mazhar 'Ali Khan (1846). Photograph: The British Library Board

A Panorama of Delhi by Mazhar 'Ali Khan (1846). Photograph: The British Library Board

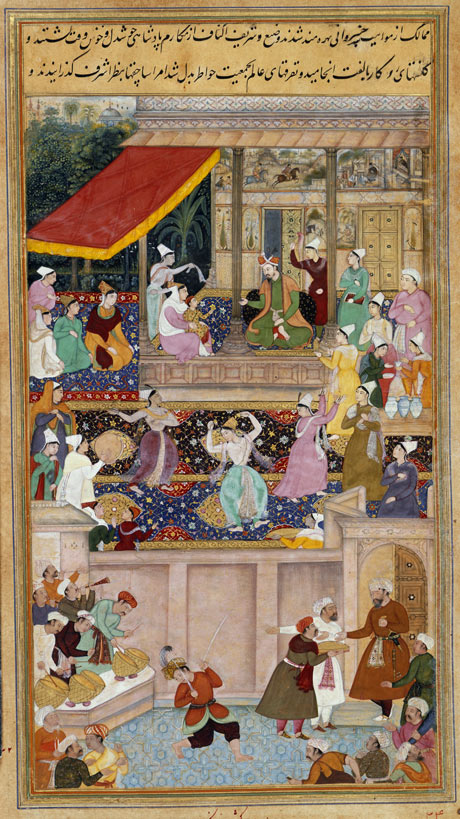

Both the good taste and the power of patronage are clearly visible in the spectacular show on the Mughals which opened recently at the British Library. In some ways it is quite an old-fashioned show – a blockbuster survey of 300 years of imperial achievement rather than the more aesthetically focused exhibitions that have become the norm of late. Two years ago, the British Library mounted a show on a single manuscript of the Ramayana produced in Udaipur. Since then the Metropolitan Museum in New York has put on a landmark exhibition, Wonder of the Age, which brilliantly reworked the history of Indian painting by paying due attention to the artists who produced the great miniatures rather than the patrons or the courts in which they were produced. By contrast, this BL show, more conventionally, uses the art to tell the story of the dynasty: its foundation, its growth, its social and court life, its literary, astronomical and scientific achievements and finally the melancholy story of its decline.

The exhibition nonetheless contains many surprises. One of the most important is the emphasis it places on the striking liberalism of the best of the Mughals. The Mughal empire was effectively built in co-operation with India's Hindu majority, and succeeded less through force than negotiation. The most interesting and imaginative of the emperors, Akbar was a free-thinking humanist who strove for the reconciliation of the different peoples and sects of his empire. He succeeded in uniting Hindus and Muslims in the service of a multi-ethnic, multi-religious state, promoting Hindus in his civil service, marrying Hindu princesses and entrusting his army to the Rajput ruler of Jaipur. He ended the religious tax paid by non-Muslims under sharia law, commissioned translations of the great Indian classics from Sanskrit into Persian and filled his court with artists and intellectuals of all faiths and ethnicities. Indeed, Akbar personally took on many Hindu practices and even became a vegetarian. The BL show contains many examples of the Mughals' interest in the Hindu faith of their subjects, including beautifully illustrated translations of the Mahabharat and the Upanishads, which the Sufi prince Dara Shikoh named the Sirr-i Akbar, the Greatest Secret, and which he speculated was the work referred to in the Qur'an as the "Kitab al-maknun" or the Hidden Book.

The Book of Pigeons, by Valih Musavi (1788). Photograph: The British Library Board

The Book of Pigeons, by Valih Musavi (1788). Photograph: The British Library Board

Christianity also fascinated the Mughals. In 1580 the emperor Akbar invited to court a party of Portuguese Jesuits from Goa, and allowed them to set up a chapel in their quarters. There they put up two paintings of the Madonna and Child, before which, to the astonishment of the Portuguese, Akbar prostrated himself. He also joined in the Jesuits' Christmas festival, when a crib was set up in the palace accompanied by Persian placards proclaiming "Gloria in Excelsis Deo". Akbar interrogated the Jesuits about Christ's exact role in the Last Judgment and, on one occasion, dressed in Portuguese garb and spent an evening listening to madrigals. The BL exhibition displays some of the original manuscripts of the Jesuits' excited reports of their discussions with the emperor, as well as some of the texts they wrote in their attempts to convert him to Christianity. In one letter, Fr Jerome Xavier reports to his masters in Goa that "we remain nearly all night in conversation with Akbar, relating many things of Christ our Lord and his saints."

The illustrated Bibles and texts brought by the Jesuits led to frescoes of Christ, Mary and the Christian saints being painted not only in the royal enclosure in Fatehpur Sikri but also on Mughal tombs, harems and caravanserais across the realm: "[the emperor] has painted images of Christ our Lord and our Lady in various places," wrote one Portuguese correspondent, "and there are so many saints that … you would say it was more like the palace of a Christian king than a Moorish one." By the end of Akbar's reign, a mural of the nativity even filled a wall of the emperor's private chamber, and miniatures and ivory plaques of Christian subjects had become a major part of the Mughal atelier output, some wonderful examples of which are on show.

Yet perhaps the biggest surprise of this show is less to do with the Mughals themselves than the British Library and the sheer richness of its Mughal collection. Although this exhibition might appear to be a carefully gathered selection of the greatest masterpieces of Mughal art, in reality it is overwhelmingly a display of the masterpieces the BL owns: of the 215 objects on display, only 20 are externally sourced loans. Indeed, so vast is the Mughal collection in the BL that even the curators have only a partial sense of exactly what it contains. The Persian library of the Red Fort, looted by the British after the Great Uprising of 1857, much of which ended up here, has still to be fully catalogued. I was told by one BL staffer that a team is only now beginning to work on listing what they have. The BL's holdings also include some remarkable private collections, the most spectacular being that of an 18th-century East India Company merchant named Richard Johnson, who was an early admirer of Mughal miniatures. The curator of the show, Malini Roy, told me that in order to choose what to include she spent six months randomly calling up five boxes of Mughal material a day from the BL's deepest vaults.

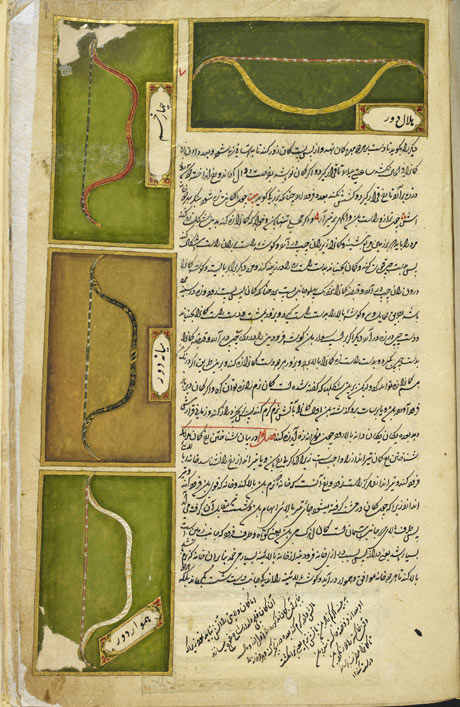

An Islamic archery manual. Photograph: The British Library Board

An Islamic archery manual. Photograph: The British Library Board

The result is a wonderful mixture of old favourites and new discoveries. Highlights include such familiar images as the weighing of Shah Jahan on his 42nd birthday, last seen at the Padshahnama show in 1997, and the famous image of Muhammad Shah Making Love, the only known erotic image of one of the emperors, which appeared in a show on Indian portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery two years ago. But amid such familiar images are illustrations never seen before. Notable are Shah Jahan's cook books, guides to perfume making, the art of pigeon keeping and "How to Be a Gentleman", as well as the "Encylopedia of Marvels" and the "Book of the Affairs of Love".

The result is one of the most magnificently mounted shows ever put on by the BL. As so much of the material comes from its own collections, economies made on bringing in loans have allowed the designers to spend lavishly on presentation. While the opening room, with its twanging sitars and latticed jail screens, gives one the sense of walking into an upscale Indian restaurant, the impressive central hall – dedicated to portraits of the 15 major Mughal emperors, under the silhouette of the statue of a fully chain-mailed Mughal warhorse and flanked on all sides by wonderful calligraphic banners – is striking. So is the combination of superbly lit and framed miniatures and the glass-fronted cabinets full of Mughal treasures, such as a jade terrapin, the wine cup of Shah Jahan and the wonderful gilt crown of the last emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar.

The hanging allows one really to engage with the miniatures and peer into their depths – these rectangles of intensely painted manuscript, gem-like in their detail and colour, which were designed to be looked at in an album, and passed from hand to hand in court. For all the public spectacle of the empire, with its crowded durbars and noisy processions, the miniatures of the Mughals are a private and intimate art, produced by a small group of skilled artists who seem to have moved from fort to fort. As a demonstration of the irresistible beauty of the art of the miniature painter and a record of an often overlooked dynasty, Mughal India: Art, Culture and Empire is unlikely to be matched for many years. Don't miss it

("Book of Pigeons" print might also be called "Book of Pairings!")

Interesting reference to the Upanishads.

Id love to see this exhibition, but might have to content myself with the book catalogue instead!

("Book of Pigeons" print might also be called "Book of Pairings!")

Interesting reference to the Upanishads.

Id love to see this exhibition, but might have to content myself with the book catalogue instead!